Beat the heat

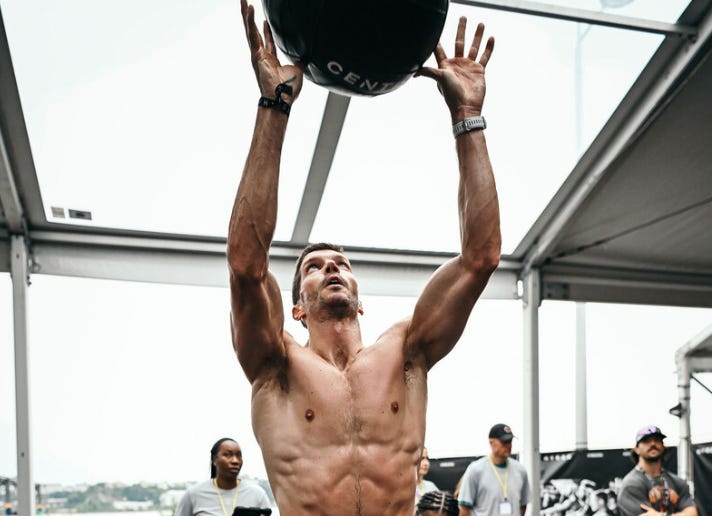

Stephen Pelkofer is a high-level Hyrox athlete and full-time coach who brings a rare combination of analytical rigor and hands-on experience to the sport. After nearly a decade as a data scientist, he shifted careers to focus fully on training — blending science, experimentation, and competition. Through his racing, coaching, and writing, he’s become a thoughtful voice in the hybrid community.

The Hybrid Letter spoke with Stephen about heat acclimation, what science says about its benefits, and how athletes can adapt safely and effectively.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Hybrid Letter: Can you tell us a bit about your athletic background and how Hyrox first got on your radar?

Stephen Pelkofer: I grew up obsessed with basketball. From age 10 into my early 20s, that’s all I did. I earned a full ride to Northern Michigan University, a Division II school, and played there for a year before transferring to UW Stevens Point, a Division III program. That was a much better fit—we won the national title my junior year, which was incredible.

After college, I focused on my career in data science but still played in a competitive men’s league. It was serious, but nothing matched the intensity of organized ball. I kept training hard but without a goal—mostly just to feel good. I wasn’t an endurance athlete.

One day, I was venting to my brother, who’s into CrossFit, about having nothing to compete in anymore. A couple of weeks later, he told me about Hyrox. I checked it out right before the 2023 World Championships in Manchester. I watched the livestream and was instantly hooked. You could tell how much of a grind it was, and I was drawn to that.

I started training right away, and my first race was in Dallas in 2023. I’ve been hooked ever since.

THL: You’ve been writing The Threshold Lab Newsletter. What motivated you to create that?

SP: In data science, I was always reading research and figuring out how to translate it into something non-technical audiences could understand. Writing made that even easier—you can refine, break things down, and explain them clearly.

I realized I had a knack for turning complex information into actionable insights. And I’ve always been obsessed with learning. In every job, the moment I stopped growing, I knew it was time to move on.

When I shifted to training, it felt natural to apply those skills to something I loved—understanding methodologies, experimenting with them myself, and eventually using them with athletes. I like the blend of “lab science” and “field science.” Learn something, apply it, see if it works.

I don’t claim to be an expert in one subject, but if you put in the time, you can build a solid understanding across many. That versatility—a big toolbox rather than one specialty—has been valuable.

THL: One of your recent articles is about heat acclimation. How does heat impact performance?

SP: Moving from Wisconsin to North Carolina was my first real exposure to Southern summers. I had a choice: complain about the heat or lean into it. That’s when I started digging into research.

I’d heard a few Hyrox Elite 15 athletes mention they were doing heat acclimation. Jon Wynn, for example, talked about using a core temperature sensor. That caught my attention.

There’s a lot of research on this, especially in cycling. That sport seems ahead of the curve on heat and altitude adaptation, maybe because performance is easier to measure or because there’s more money. Either way, the takeaway is clear: you can build adaptations quickly, often within two weeks.

THL: What benefits do athletes get from heat acclimation?

SP: One is an increase in blood plasma volume. Your heart can pump more blood per beat, delivering more oxygen to your muscles. Another is better thermoregulation—your body cools itself more efficiently. Well-acclimated athletes often sweat more, even in cool conditions.

Historically, research showed heat training improved performance in the heat. But newer studies ask if it also helps in normal or cool conditions. Results are mixed, but one cycling study showed improvements in both. That’s exciting for athletes like us who compete indoors, often in humid convention centers.

People also call heat training the “poor man’s altitude camp.” You don’t need to travel—you can just throw on layers or train in a hot garage.

THL: What takeaways did you learn from the research?

SP: Be smart about it. Hydration before and after becomes more important, and nutrition plays a bigger role. Most athletes do easy sessions in the heat, not high-intensity intervals. That makes sense—you still need to hit your hard sessions at the right pace or power.

So I add easy aerobic sessions in the heat—bike, rower, skier, or run. Since output doesn’t matter as much, you can train effectively while also building adaptations.

THL: How can athletes safely implement heat training?

SP: Start easy and short. Some elites will tack heat sessions onto long workouts, but I wouldn’t recommend that for recreational athletes.

If you’ve got an easy aerobic day—say 60 minutes of running or biking—move some of it to a hotter environment. Two or three times a week is a good start.

Try it for two to three weeks. Progress the time gradually, but don’t make it harder. Adaptations can happen within 1–2 weeks. Beyond that, the research is less clear, so don’t overdo it.

Start with 20 minutes twice a week. After two weeks, move to three sessions. Then test yourself in cooler conditions with a time trial or benchmark workout.

THL: What do you tell your athletes about running in the heat?

SP: Throw pace out the window. I love data, but this summer I made a rule: on easy runs in the heat, I don’t look at pace or power.

If you can run six-minute miles in a 10K, your easy runs might be 8–9 minutes per mile. If those slip to 9:30 in the heat, it doesn’t matter. Heart rate is naturally higher, so pace isn’t the point.

What matters is time—time on feet in tough conditions. Can you go from 20 minutes to 30 minutes over a couple weeks? That’s the progression.

THL: What about fuel and hydration?

SP: You should always pre-hydrate and pre-fuel. In the heat, electrolytes are more important. And pre-hydrating doesn’t mean slamming water right before—you need to build it up in the hours before, or even the day before for long sessions.

Research shows it’s crucial to get carbs in immediately after endurance sessions, ideally with protein too. That combo is key for recovery. In heat, you’re losing more water, so rehydrating afterward matters even more.

Most of us don’t have coaches monitoring us. But you can weigh yourself before and after. If you’ve lost more than 2–3% of your body weight, that’s a red flag—you need to refuel and rehydrate more.

Respect the heat. Don’t jump into 90-minute sessions every day. Be intentional with fueling and hydration, get ahead of the session, and nail that post-workout window with carbs, protein, and fluids.

THL: What warning signs should people watch for?

SP: Pay attention to how you feel. If you finish shaking, completely wiped, or overly fatigued, that’s a signal—take a day off, eat extra carbs, and hydrate.

Tracking helps. Write down what you did: water intake, electrolytes, body weight. Were you prepared, or did you just wing it?

It comes down to respecting the conditions and knowing your limits. My philosophy is: no single session matters if you can’t stack them over time. Consistency is what builds fitness.

So don’t crush some “hero workout” in 90-degree sun to prove something. Play the long game and give your body what it needs.

THL: Have you tried any products to track heat adaptation?

SP: There’s a product called Core—a thermal sensor that tracks core body temperature. I haven’t used it, but it’s interesting.

The gold standard is a rectal thermometer, which most people won’t do. Core attaches to your heart rate strap and estimates temperature throughout a session. Triathletes are using it for heat adaptation.

It’s not perfect, but paired with heart rate and pace or power, it gives a useful picture of how your body handles heat. It even provides a “heat acclimation” score.

I’d be surprised if more Hyrox Elite 15 athletes don’t start using it. Tracking internal data in real time and tying it to performance could be a big edge, especially in hotter races.

You can follow Stephen on Instagram or subscribe to his newsletter.

If you are reading this newsletter, you may be iron-deficient

According to scientific studies, an alarmingly high number of endurance athletes suffer from iron deficiency. One study of 193 serious young endurance athletes, for example, found iron deficiency in 31% of men and 57% of women. Another study of 38 runners and triathletes found similar levels of iron deficiency.

Several factors are at play. First, endurance athletes need more iron than the general population. The recommended daily intake of iron — 8 mg for men and 18 mg for women — is not sufficient for athletes engaged in hours of endurance training each week. Iron facilitates oxygen transfer and the production of red blood cells, so more iron is required to support higher training volumes.

Further, endurance athletes lose iron as a result of training. A small amount of iron is lost through sweat. Athletes engaged in a lot of running can also lose iron through foot-strike hemolysis, where the impact injures the capillaries in the foot. High-intensity training can also cause microscopic bleeding in the digestive tract, leading to iron loss through gastrointestinal bleeding. The loss from any one sweaty workout or long run is not large, but the iron losses can add up for athletes who train frequently. Exercise also results in the production of the hormone hepcidin, which inhibits iron absorption.

According to a November 2023 research paper, "high-intensity and endurance training, can result in a substantial depletion of the body’s iron stores with reductions of up to 70% observed when compared to the general population."

Even moderate iron deficiency can have a major impact on performance in endurance sports. Lower iron is associated with lower VO2 max, slower 2K row times, and overall decreased endurance capacity. Correcting iron deficiencies can result in improved endurance performance of 2-20%.

If you suspect you might have an iron deficiency, consult your doctor. Iron supplements are cheap and widely available. They usually can reverse exercise-related iron deficiency within a few months. But iron deficiency can also be related to other health issues. And there are potential side effects, including GI distress, and ingesting too much iron can be dangerous.

Athlete of the Week: Peter Edgar

Name: Peter Edgar

Age: 37

Hometown: Chatham, NJ

When did you start hybrid training? I started CrossFit in 2014 and have been training that way for over a decade now. Once I heard about Hyrox, I began adding running into my training. My first Hyrox was DC in 2024, and I’ve been hooked ever since. I think I’ve done over 10 at this point.

Favorite race to date and why? World Championships doubles this year with my partner Beau. We were able to podium in by far the hardest competition we’ve ever faced in the 40–49 age group, and got that third place for the U.S.

Do you have a race goal? Next goal is to qualify for the 2026 Hyrox World Championships in Stockholm. Longer term, I’ve got a lot more work to do, but a sub-60 solo pro would be dope.

Favorite station? Wall Balls. I guess I like them from my CrossFit days, but also it’s the time in the race to empty the tank and give everything you have left.

Least favorite station? Burpee broad jump. The run after suckssssss.

What is something you wish you knew before you started training and racing? From a training perspective, I wish I knew earlier the importance of Zone 2/easy workouts. I was going too hard too often. From a racing perspective, the biggest thing is remembering to have fun and not get too caught up in results and times. If it’s not fun, we’re not doing it right.

Living in Florida I was trying to drink a lot of water, pre hydrate before getting out there. I started to get light headed and a friend reminded me we can overhydrate and need to add some electrolytes. I don’t do any of those “power drinks.” Problem solved.