How to train your brain to crush Hyrox

Dr. Josephine Perry, a sport psychologist and founder of Performance in Mind, has spent years helping athletes unlock what their bodies can do by training the one thing most overlook—the brain. An endurance racer herself, she knows how easily the mind can shut you down before your body is done.

We spoke with Dr. Perry about pushing past perceived limits, making effort feel easier, and keeping your threat system quiet.

This interview is edited for length and clarity.

The Hybrid Letter: How did you become interested in sports psychology?

Dr. Josephine Perry: I used to do Ironman racing, which for me has now been replaced by Hyrox. Back then, Ironman was the “one big thing” I trained for each year. I remember racing in Melbourne, Australia—the waves were terrifying. I was scared. Then the announcer said, “You can’t control the waves, but you can control how you feel about them.” That was a lightbulb moment.

It made me realize that if I thought differently about racing, I might perform better. Physically, I’m not built to be an athlete. I have scoliosis—my spine is twisted in two places, breathing is hard, and I’m often in pain. But that moment in Melbourne showed me I couldn’t change my body, but I could use my brain.

When I got back to the UK, I started thinking more about the role of the mind in sport. Thirteen years ago, there wasn’t nearly as much material on it as there is today, but I read everything I could. That’s when I discovered you could actually train to be a sports psychologist. I went back to university, did a master’s in psychology, and loved it. Then I did a sport psychology master’s as well. To fully qualify, I had to do three years of supervised practice. I committed to the process and never looked back.

THL: Through that process, what was the biggest shift in your thinking about athletic performance?

DJP: Our brains are designed to protect our bodies. At the core is the amygdala, whose job is to keep us alive—by predicting danger, triggering emotions, and activating the body to respond. One way it does this is by shutting us down earlier than necessary when it comes to physical effort. For most of human history, conserving energy meant survival.

THL: Why train your brain?

DJP: Because sport pushes us in ways our brains weren’t built for. The brain is constantly scanning for threats, trying to slow us down, control heart rate, conserve energy “just in case.” Physically, we can do more than we think—but our brains hold us back. Sports psychology helps athletes unlock that potential while staying safe.

THL: What do you notice in athletes who excel mentally?

DJP: Some people are naturally able to push incredibly hard—often those who are intelligent and perfectionistic. They set the bar high and work relentlessly. But even they battle their brain’s protective system.

Others are exceptional at overriding that system. Think of the Brownlee brothers dragging each other across the finish line—they’d trained themselves to push past shutdown.

One way to see it: in a VO₂ max test, when an athlete stops, convinced they’re done, muscle biopsies show about 30% of energy reserves remain. The brain has simply shut things down early. My work is about helping athletes access more of that reserve.

The latest theories say two things matter most: increasing motivation and reducing the perception of effort. Motivation takes you far. But once you’ve maxed that out, making the effort feel easier is the real unlock.

THL: How can athletes reduce their perception of effort?

DJP: By finding strategies that make things feel less hard, so the brain eases off. Caffeine works for some. For others, not at all.

Smiling is one of the simplest tools. When you smile, your brain interprets the effort as easier. In one study, cyclists shown smiling faces performed better than those shown neutral ones. In HYROX, smiling at spectators—and having them smile back—can give a real lift.

Chunking is another: breaking the event into smaller pieces. HYROX is great for this since you can take it station by station.

And sometimes it’s very individual. One of my athletes said, “When something hurts, focus on the parts of your body that don’t.” I tried it in a race. My back was in agony, but my feet felt fine. Shifting focus worked brilliantly.

THL: How do you help athletes overcome bad races or training sessions?

DJP: There’s a strong sense of redemption. They’ll remember how awful it felt and think, I am not going through that again. That negative filter—wired into our brains—pushes them to create a new strategy.

Scarcity also plays a role. Ironman races used to sell out in minutes, but now Hyrox has waitlists of 10,000. Just getting a spot raises the stakes. It’s not, I’ll do another one if this goes badly. Athletes feel a higher level of commitment—and with it, a powerful drive for redemption.

THL: How does goal setting impact psychology and performance?

DJP: The threat system is key. That’s the part of the brain that fuels negative self-talk, changes physiology, and makes you want to pull back. Outcome goals—I must podium, I must go sub-1:30—are one of the biggest triggers. They put the threat system on edge before you even start. A setback or two, and it tips into overdrive.

But if you show up with no identity tied to the outcome—say, you’re new to Hyrox—you’re free. There’s no expectation. That keeps the threat system calm.

That’s why I emphasize mastery over outcome. Focus on actions or qualities within your control: I want to persevere. I want to stay strong. These intentions guide you in a healthier way.

With outcome goals, if halfway through you realize you’re off pace, your brain says, What’s the point? I’ve already failed. But if your goal is, I want to finish all 100 wall balls no matter how long it takes, the threat system stays quiet. Ironically, that’s how you’re more likely to hit your performance target.

THL: What’s a typical conversation like with one of your athletes before a big race?

DJP: Three or four days before, we’ll do a confidence session. We don’t ignore outcome goals—you want to qualify for Worlds, or place top-10. That’s fine. But then I ask, What performance would it actually take to get there?

That’s where we shift to inputs: What’s in your control? Did you support your partner fully? When you wanted to stop, did you push harder? If your partner struggled on the sled, did you step in? Those are the behaviors you own.

If you don’t hit them, you roll them into the next race. But when you do, you know you’ve performed well, regardless of the scoreboard.

THL: What else do you encourage athletes to do around races?

DJP: I stress the post-race session. Many athletes hit post-race blues. You’ve built your life around that one day, and then—suddenly—it’s over. Even if you did brilliantly, there’s often a “what’s next?” crash.

The way through is to review what went well, plan improvements, and set new goals. That keeps you grounded, progressing, and avoids the emotional drop-off.

You can follow Dr. Perry on Instagram or read the 10 Pillars of Success.

A new elite layout is the first step in Hyrox’s push to become an Olympic sport

Hyrox co-founder Christian Toetzke has been open about his ambitions to have Hyrox included in the 2032 Summer Olympics in Brisbane, Australia. Toetzke noted that Hyrox is already more popular than some existing Olympic sports, like the modern pentathlon — an obscure event that features fencing, freestyle swimming, obstacle course racing, laser pistol shooting, and cross-country running.

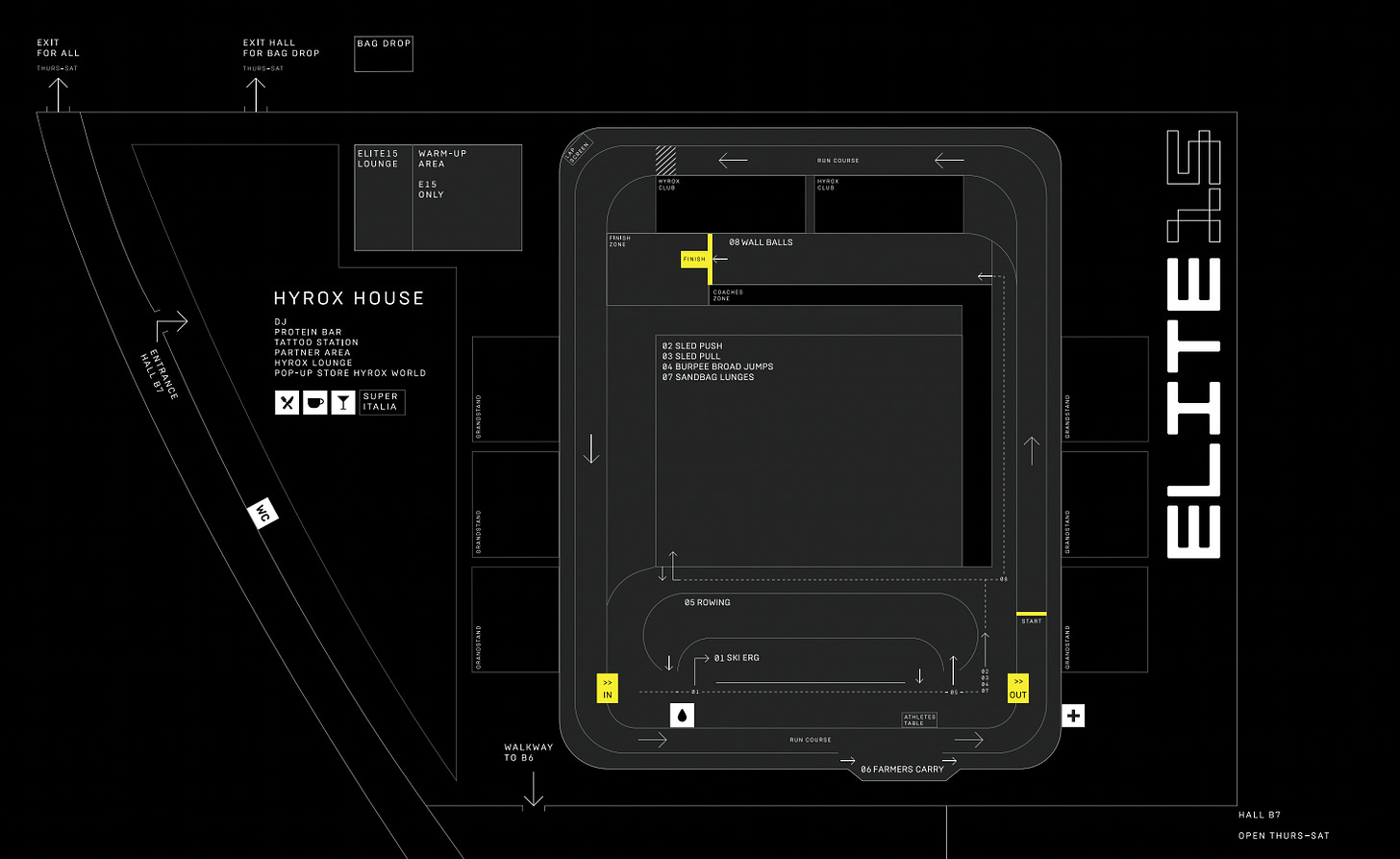

Among the many requirements for Olympic sports is standardization. Today in Hamburg, Hyrox is debuting a new standard course layout for elite athletes in the year’s first major. The course, which will only be used for elite races, features a shorter 200-meter track, a special lane for farmer’s carry, and grandstands on both sides.

The races will be broadcast live on YouTube today at 9:30 a.m. Eastern (Women’s Elite 15) and 12:30 p.m. Eastern (Men’s Elite 15). The recording is available immediately after the event.

Athlete of the Week: Jessica Garcia

Name: Jessica Garcia

Age: 36

Hometown: Miami, FL

When did you start hybrid training? I started hybrid training after realizing I didn’t want to be limited to just one style of fitness. I began in bodybuilding, but I wanted more—I wanted strength, endurance, and functional capacity all at once. Hybrid training challenged me to move past aesthetics and become well-rounded: able to run long distances, move heavy loads, and stay resilient under pressure. It fit the mindset I’ve carried from law enforcement, the military, and motherhood: you have to be ready for anything.

Favorite race to date? My favorite race so far has definitely been a Deka Fit I competed in with my son. Sharing the floor with him, side by side as partners, was an experience I’ll never forget. We pushed each other through every station, celebrated the small wins as we went, and crossed the finish line taking first place together. Winning was incredible, but what meant the most was bonding over the work, the energy, and the spirit of competition. That race will always hold a special place in my heart.

Do you have a race goal? Yes—my current goal is to compete in the Women’s Pro division in Hyrox, the only division I haven’t done yet. I’d also love to race internationally one day and see how I stack up against athletes around the globe. My long-term vision is to keep proving that everyday athletes can achieve extraordinary things when they commit to the process.

Favorite station? The sled push. It’s pure grit and power—no shortcuts, no easy way out. It forces you to dig deep and trust the work you’ve put in. For me, it symbolizes the grind of life: heavy, hard, but always movable if you keep driving forward.

Least favorite station? Wall balls, for sure. They look simple, but when you’re fatigued, they demand perfect coordination, accuracy, and endurance. They’re a humbling reminder that even small movements require discipline.

Things you wish you knew before you started racing? I wish I’d known the importance of recovery, fueling, and pacing. Early on, I thought more training was always better. Over time, I’ve learned that nutrition, rest, and smart programming are just as crucial as hard work. I also wish I’d known how supportive and welcoming the hybrid community is—you don’t have to do this alone. Surrounding yourself with the right people makes all the difference.

Like so much of how the articule put a big impact of how to calm the mind while your body is getting to the limit.

So important in sports.

Thank you for this! This applies in so many areas of life.