What Your Blood Knows

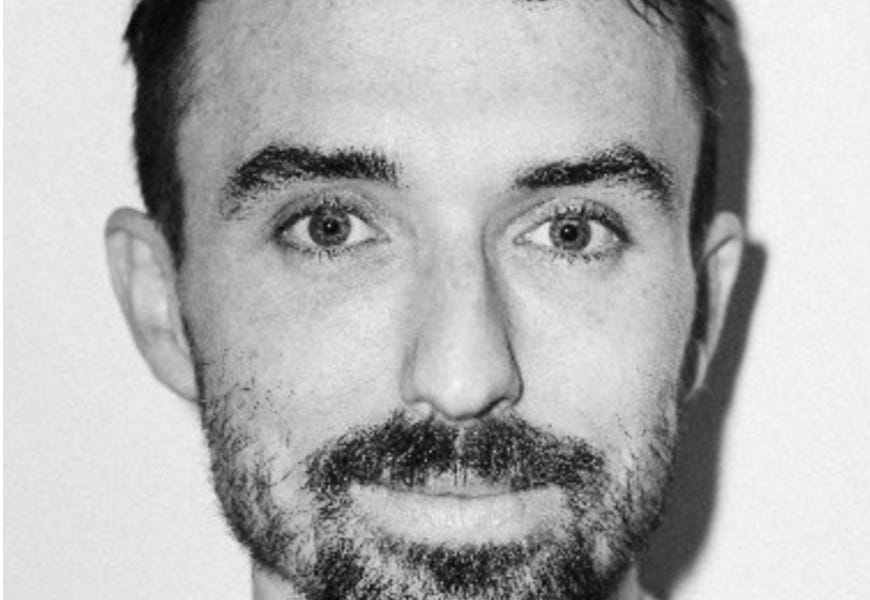

Robby Wade is a competitive Ironman athlete and the founder of Rythm Health, a blood-testing company that helps athletes better understand the connection between training, recovery, and nutrition. He spoke with The Hybrid Letter about the biomarkers worth watching, the pitfalls of modern health culture, and why the basics still matter most.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

The Hybrid Letter: What got you interested in blood testing?

Robby Wade: My dad had a kidney transplant when I was a kid, and for years we had a dialysis machine set up in the living room. This was around 2000 or 2002, so he was filtering his blood at home. Mobile phlebotomists came over constantly, and one of our kitchen cupboards was full of dialysis supplies, blood pressure machines—everything.

In a way, our house was like a mini lab. So it never felt strange to me to be around medical equipment or blood testing; it was just part of daily life. My dad was a patient for most of my childhood, and that had a big impact on me. I’ve always been determined to stay healthy—to not be a patient myself.

When I think back on it, what stands out is that my dad didn’t necessarily make bad choices; he just didn’t know what he didn’t know. That experience shaped the way I think about health and knowledge today.

THL: Blood testing has become very trendy. Are there aspects of the industry and associated health claims that give you pause?

RW: Yeah, I think the thing to understand about me is that I have a pretty different view from a lot of people in the health space. I’m definitely not a biohacker. I’m a big believer in the fundamentals — you need to train, eat enough protein, get some magnesium, spend time in the sun, move more. I’m not one of those people with 35 different supplements.

Most people just need to get the basics right. And I also think the reason to be healthy 80 percent of the time is so you can have fun the other 20 percent — go out with your friends, have a couple of glasses of wine, enjoy life.

A lot of what’s happening in health right now feels a bit sterile, like it’s about being a hermit for as long as possible. That’s not interesting to me. I think you should optimize your health most of the time so that when those “when in Rome” moments come along, you can let your hair down and actually enjoy them.

THL: You’re an athlete — can you talk a bit about your background and how that’s influenced the way you think about health?

RW: My athletic background was kind of an accident. I got into it pretty late. I started doing triathlons when I was 28 or 29. Before that, I went to the gym and trained, but I never thought of myself as athletic. I had this idea when I was younger that people were just born with that talent — that you either had it or you didn’t. Eventually, I realized it’s more of an input–output thing: if you train hard, you get good. Obvious now, but it didn’t feel that way when I was a teenager.

Once I started triathlon, I took it seriously. I raced at the Ironman World Championships in 2024, finished as the top Australian in my age group, and ranked ninth in the world.

For me, the interesting part wasn’t just the competition — it was understanding what it actually takes for the body to perform at a high level. You can read about that stuff in books, but living it is different. Training and racing like that showed me what really moves the needle in human performance and what doesn’t.

I’ve kept at it because I enjoy it. I tend to gravitate toward longer, more grueling races — that’s probably just my stubbornness. I’m much more of an ultra or Ironman type than a sprinter.

THL: What’s a blood marker that people don’t pay enough attention to?

RW: One that stands out is thyroid function — especially free T3. It’s a really good proxy for whether you’re eating enough.

Most people hear constant messaging about eating less, but for athletes training a lot, not eating enough is often the bigger problem. That’s something I’ve noticed again and again. I was lucky in that I prioritized fueling and nutrition pretty early. But there’s a lot of body dysmorphia out there — this idea that eating more is somehow wrong. For sedentary people, maybe that makes sense. But for athletes, it’s one of the biggest challenges when it comes to recovery, injury prevention, and performance.

You can see all of that reflected in thyroid markers. When your thyroid slows down — what’s called low energy availability, or RED-S, relative energy deficiency syndrome — it’s basically your body saying it doesn’t have enough energy to run everything. It starts shutting down what it considers “non-essential” systems: bone remodeling, hormone production, fertility. It’s a signal that you’re under-fueling, and it’s more common than most people think.

THL: What are some other blood markers you think athletes could benefit from tracking?

RW: Testosterone is a big one, for a lot of reasons. Inflammation markers like CRP are also critical. Iron is huge. And vitamin D — that’s another big one people often overlook.

What’s interesting about vitamin D is how it ties to magnesium. Magnesium actually increases your body’s ability to absorb vitamin D, so when someone’s vitamin D is low, it’s often because they’re magnesium deficient. And that matters, because magnesium affects almost everything — bone health, energy production, recovery, muscle function. If you’re low on magnesium, your performance is going to suffer across the board.

THL: Many people only get their blood tested once a year, if that, through their doctor. What’s the benefit of testing monthly?

RW: Athletes have different problems than the average person. Do you have to test monthly? No, not at all. But it’s like tracking your sleep — you don’t need to, but if you do, you get better trends and a clearer picture to make decisions from.

People often underestimate how dynamic blood markers can be. Take iron, for example. If your iron is low, you can’t just take a supplement and assume you’ve fixed it. Absorption varies depending on your body — your size, weight, training load — so even if you increase your levels by 15 percent, you might still be well below optimal. It can take months of adjustment and calibration to get it right.

That’s where monthly testing helps. You start to learn patterns — when I do this, this happens. You can actually see how eating 1,500 more calories improves your thyroid, or how a change in training affects recovery markers. It creates a feedback loop where you’re not guessing anymore.

The other piece is accountability. If your coach tells you to eat more protein and you know you’ve got another test coming up in two weeks, you’re more likely to follow through. It becomes a bit of a game — you want to see improvement, not backslide.

For athletes, the stakes are higher. The cost of being out of range on key biomarkers can be real. Everyone says you can’t stay “optimal” all the time, but that’s exactly what athletes are chasing — staying as close to that line as possible, as consistently as possible.

You can follow Robby on Instagram.

Video of the Week: The surprising truth about heart rate zones and Hyrox

Heart rate training is very popular in hybrid sports, as it has proven highly effective in pure endurance events like running and triathlon. But in a new video by WOD Science, Gommaar D’Hulst explains how heart rate can be a misleading data point in functional fitness events like Hyrox. D’Hulst presents evidence that heart rate spikes while performing functional fitness movements like burpees or wall balls are influenced by body position and are not a clear indicator of intensity.

Hybrid Athlete of the Week: Amy Brown

Name: Amy Brown

Age: 45

Hometown: Pittsburgh, PA

When did you start hybrid racing? I’d been a marathon runner for years but always loved strength training. I was chasing a sub-3-hour marathon for what felt like forever. My strength coach mentioned HYROX to me back in 2022—he kept saying, “You’d be really good at this.” But I get so fixated on my goals that I didn’t want anything to interfere with my marathon training. He kept bugging me, and I finally said, “Okay, I’ll try,” but honestly, I had no real intention of actually doing one. Then a local gym hosted a comp in early 2024, and I signed up on a whim. I ended up winning and was immediately hooked.

I’ve always felt like I never quite fit into the marathon space—I was always bigger and more muscular than the women I lined up against who ran at my pace. So when I did my first race in NYC, I remember thinking, wow, this is where I belong. It blends the two things I love most—running and strength—so beautifully.

Favorite race to date? World Championships in Chicago this year. I was so grateful for the opportunity to race alongside the best in my division. I spent years chasing a marathon goal that never came to life, so finally reaching a big goal and realizing a dream felt incredible. It still feels surreal to call myself a World Champion. I never would’ve imagined that, after just one year in this sport, I’d be standing at the top of the podium.

Race goal? My main goal right now is to hit a 1:05, and I’m hoping to accomplish that by the end of the season. My next race is Atlanta, and I’m aiming to defend my World Champion title at Worlds this coming year. With the competition getting fiercer than ever, I know this is the time to step up and go into Worlds with full confidence.

Favorite station? It’s a toss-up between the SkiErg and the sled push. I love the first part of the race with the run–ski–run combo—coming from a long-time endurance background, that’s where I feel most in my element. But I also love the sled push because it’s the first point in the race where I’m really challenged, and it’s historically been one of my best-ranked stations.

Least favorite station? Without a doubt, the wall balls. I’ve worked so hard on them, even built up to doing huge unbroken sets in the gym. But no matter how much I practice, they always seem to humble me on race day.

Things you wish you knew when you started racing? I come from a high-volume marathon background, often running 80–90-mile peak weeks during training. I’m used to low and slow. But the intensity in HYROX hits differently—it’s not just running with strength work; you have to specifically train for that kind of effort. Even in races, it’s easy for my marathon mind to take over and not push as hard as I need to.

When I first started, I tried to keep my running volume at 50–60 miles a week, but I think that was actually holding me back. It wasn’t allowing me to get stronger where I was weakest—in the gym. Now, I only run about 30–40 miles a week, and I feel so much better. I’ve made way more progress this way. There’s a lot of mixed advice out there about how much volume you need to improve, but for me, less has definitely been more.